Above: A portrait of Kristina, painted by French court painter and portrait artist Sébastien Bourdon, painted circa 1650.

NOTE: Trigger warning for mentions of violence, r*pe, and childhood trauma. A lesser warning: this is a LONG read.

Kristina Alexandra, born Kristina Augusta Vasa, (1626-1689) ruled over the Swedish Empire as Queen regnant of Sweden (she took the coronation oath as King, which was her official title) from 1632 upon the death of her father, King Gustav II Adolf of Sweden (although Kristina did not gain actual authority until she came of age on her eighteenth birthday in 1644), until her abdication on June 6, 1654. Kristina's full title was: Kristina, by the grace of God, Queen of the Swedes, Goths and Vandals, Grand Princess of Finland, Duchess of Estonia and Karelia, and Lady of Ingria. In the early 1650s, due to Sweden's territorial expansion, her title was expanded to include Duchess of Bremen-Verden and Stettin-Pomerania and Princess of Cashubia and Vandalia.

Kristina was born at Tre Kronor Castle in Stockholm on December 8/18 (Old Style), 1626. There was some confusion over her gender at birth: she was covered in hair (lanugo) and a birth caul and cried with a strong, loud voice, causing the midwives to believe that the royal newborn was a boy. When the "mistake" was revealed, King Gustav was surprisingly delighted to have a daughter and was very close to Kristina, although Maria Eleonora, who was already very emotionally and mentally unstable and probably suffered from postpartum depression after Kristina's birth, would deeply resent Kristina for being a girl; and as a baby, she was subjected to several suspicious "accidents", one of which resulted in her collarbone breaking and never healing properly, which left one shoulder higher than the other for the rest of her life. Kristina believed that this resulted from one of her nursemaids dropping her on purpose, probably at her mother's orders.

"Le Roi obtint enfin ce qu'il avoit si fort desiré dans un voyage qu'il fit en Finlande, où la Reine, qui l'accompagna, se trouva grosse de moi dans Abo; ce qui leur donna à tous les deux une fausse joye, puisqu'ils se persuadérent qu'en accouchant de moi, elle accoucheroit d'un Fils. Elle eut des songes qu'elle crut mystérieux, & le Roi en eut de-même. Les Astrologues, qui sont toujours prêts à flatter les Princes, l'assurérent que la Reine étoit enceinte d'un successeur: ainsi on se flatta, on espéra, on se trompa, & on arriva enfin jusqu'au terme, SEIGNEUR, que vous avez prescrit à tous ceux qui entrent dans la vie. Déjà la Cour étoit de retour à Stockholm. Le Roi y étoit aussi; mais il étoit considérablement malade, & des Astrologues, qui se trouvérent présens, assurérent unanimement que le point de ma naissance, qu'ils voyoient approcher, étoit tel qu'il étoit presque impossible qu'il n'en coûtât la vie au Roi, ou à la Reine, ou à l'Enfant. Ils assurérent aussi que si cet enfant pouvoit survivre les 24. heures, il seroit quelque chose de fort grand."

"The King finally obtained what he had so much desired while on a journey to Finland, where the Queen, who accompanied him, was found to be pregnant with me in Åbo; which gave them both a false joy, since they persuaded themselves that Heaven would give them an heir. The Queen, my mother, assured me that all the signs deceived her, and persuaded her that by giving birth to me, she would give birth to a son. She had dreams which she thought mysterious, and the King had some of them. The astrologers, who are always ready to flatter princes, assured him that the Queen was pregnant with a successor: so one flattered oneself, one hoped, one was wrong, and one finally came to the end, Lord, that You have predestined to all who enter life. Already the court was back at Stockholm. The King was there too; but he was considerably ill, and the astrologers, who were present, unanimously assured that the timing of my birth, which they saw approaching, was such that it was almost impossible for it to not cost the King his life, or that of the Queen, or that of the child. They also assured that if this child could survive the first 24 hours, it would become someone very important."

"C'est dans une telle constitution des astres que je vins au monde. ... Je nâquis coëffée depuis la tête jusqu'àux genoux, n'ayant que le visage, les bras, et les jambes de libres. J'étois toute velue, j'avois la voix grosse et forte: Tout cela sit croire aux femmes, occupées à me recevoir, que j'étois un garçon. Elles remplirent tout le Palais d'une fausse joye, qui abusa le Roi même pour quelques momens. L'espérance et le desir aidérent à tromper tout le monde; mais ce fut un grand embarras pour les femmes, quand elles se virent trompées. Elles étoient en peine comment desabuser le Roi. La Princesse Catherine, sa Sœur, se chargea de cette commission. Elle me porta entre ses bras en état de me faire voir au Roi, et de lui faire connoître ce qu'elle n'ôsoit lui dire. Elle donna au Roi le moyen de se desabuser de lui-même. Ce grand Prince n'en témoigna aucune surprise, il me prit entre ses bras, il me fit un accueil aussi favorable que s'il n'eût pas été trompé dans son attente. Il dit à la Princesse: Remercions Dieu, ma Sœur. J'espère que cette fille me vandra bien un garçon. Je prie Dieu qu'il me la conserve, puisqu'il me l'a donnée. La Princesse, pour lui faire sa cour, voulut le flatter qu'il étoit encore jeune; que la Reine l'étoit aussi, et qu'elle lui donneroit bientôt un héritier; mais le Roi lui répondit dérechef: Ma Sœur, je suis content, je prie Dieu qu'il me la conserve. Après cela, il me renvoya avec sa bénédiction, & il parut si content, qu'il étonna tout le monde. Il commanda qu'on chantât le Te Deum, & qu'on fit toutes les réjouissances accoutumées dans les naissances importantes des premiers mâles. Enfin il parut aussi grand en cette occasion, comme en toutes celles de sa vie. Cependant on tarda à desabuser la Reine, jusques à ce qu'elle fût en état de souffrir un tel déboire. On me donna le nom de Christine. Le Ministre Luthérien, qui me baptisa (c'étoit le grand Aumônier du Roi), me marqua le front du signe de la Croix avec l'eau du Baptême, & m'enrolla, sans savoir ce qu'il faisoit, dans votre milice dès ce moment heureux. Car il est certain que ce qu'il fit, étoit contre le cérémonial ordinaire des Luthériens. On lui en fit même une affaire comme d'une superstition, dont il se tira comme il pût. Le Roi disoit de moi et riant: Elle va être habile; car elle nous a tous trompés. Aussi dès que je nâquis, je donnai un solemnel démenti aux Astrologues; car le Roi guérit, la Reine ma Mére accoucha heureusement, je me portois bien, & de plus j'étois fille. La Reine, ma Mere, qui avoit toutes les foiblesses, aussi bien que toutes les vertus de son Sexe, étoit inconsolable. Elle ne pouvoit me souffrir, parce qu'elle disoit que j'étois fille & laide; & elle n'avoit pas grand tort, car j'étois basanée comme un petit Maure. Mon Pere m'aimoit fort, et je répondois aussi à son amitié d'une manière qui surpassoit mon âge."

"It was under such a constitution of the stars that I came into the world. ... I was born covered with hair from my head to my knees; only my face, arms and legs were free. I was hairy all over my body and I had a coarse, strong voice. All this led the women who received me to believe that I was a boy. Throughout the Court they spread a false joy which, for a moment, even fooled the King. Hope and desire helped to deceive everyone; but it was a great embarrassment for the women when they found that they had been deceived. They agonised over how to disillusion the King. Princess Katarina, his sister, took charge of this commission. She carried me in her arms in such a condition to show me to the King, and to let him see for himself what she dared not tell him. She gave the King the means to undeceive himself. This great prince showed no surprise, he took me in his arms, he gave me a reception as favorable as if he had not been deceived in his waiting. He said to the Princess: 'Let us thank God, my sister. I hope that this girl will be just as worthy to me as a boy. I pray to God that He will preserve her, since He has given her to me.' The Princess, who wished to flatter him, reassured him that he was still young, as was the Queen, and that she would soon give him an heir; but the King answered her once more: 'My sister, I am content. I pray to God that He will preserve her for me.' After that he sent me away with his blessing, and he seemed so happy that he astonished everyone. He ordered that the Te Deum be sung, and that all the usual celebrations be done just as upon the important births of male heirs. Finally, he seemed as great on this occasion as he did on all those of his life. However, they delayed undeceiving the Queen until she was in a condition to suffer such a disappointment. I was named Kristina. The Lutheran minister who baptised me (he was the King's Great Chaplain), marked me with the baptismal water with the sign of the Cross, and did not know what he was doing when he enrolled me in Your militia in that happy moment. For it is certain that what he did was against the ordinary ceremony of the Lutherans. The King laughingly said of me: 'She will be clever, for she has fooled us all.' So as soon as I was born, I gave a solemn denial to the astrologers, because the King recovered, the Queen my mother gave birth happily, I was doing well, and what's more: I was a girl. The Queen my mother, who had all the weaknesses as well as all the virtues of her sex, was inconsolable. She could not stand me because she said that I was an ugly girl, and she was really not very wrong in that, for I was swarthy like a little Moor. My father loved me very much, and I responded to his friendship in a manner that surpassed my age." - Kristina in her autobiography, published by Johan Arckenholtz in 1759.

"Il arriva, peu de jours après qu'on m'eut donné le Baptême, qu'une grosse poutre tomba & faillit d'écraser le berceau où je dormois, sans me donner la moindre atteinte. Outre cet accident, on fit encore d'autres attentats sur moi. On me fit tomber exprès, on tenta mille autres inventions pour me faire périr, ou pour du moins m'estropier. La Reine, ma Mére, disoit de belles choses là-dessus, & on ne pouvoit la desabuser de ses imaginations. Quoi qu'il en soit de tout cela, il ne me reste aucun autre préjudice qu'un peu d'irregularité dans ma taille, que j'aurois pu corriger, si j'eusse voulu m'en donner la peine."

"It came to pass that, two days after my baptism, a big beam fell and almost crushed the cradle where I lay asleep, and I was not harmed in the least. In addition to this accident, I was also exposed to other attacks. I was intentionally dropped onto the floor, someone tried a thousand different ways to kill me or at least cripple me. The Queen, my mother, had her own explanations for this, and could not be persuaded otherwise. However that may be, I was not harmed other than that there is a bit of an irregularity on my back that I could have had corrected or at least concealed, if I had wished to give myself the trouble." - Kristina in her autobiography, published by Johan Arckenholtz in 1759.

Gustav Adolf had Kristina designated his heir, and the two were very close. When he was killed at the Battle of Lützen on November 6, 1632, Kristina was a month shy of her sixth birthday.

"Les prèmieres années de mon enfance n'eurent rien de remarquable, sinon une maladie mortelle, qui me vint pendant un voyage que le Roi fit aux Mines. On lui expédia un Courier pour lui apprendre mon mal. Il fit une diligence si extraordinaire pour se rendre auprès de moi, qu'il arriva en vingt-quatre heures; ce qu'un Courier n'a jamais fait. Il me trouva aux abois, et en parut inconsolable; mais enfin je guéris, et il en témoigna une joye proportionnée à sa douleur. Il en fit chanter le Te Deum."

"The first years of my childhood were nothing remarkable except a deadly illness that came to me during a trip the King made to see the mines. A courier was sent to him to tell him of my illness. He was so diligent in coming to see me that he arrived within a day, which a courier has never done. He found me at my last hour, and seemed inconsolable; but at last I recovered, and he showed a joy equal in proportion to his pain. He had a Te Deum sung."

"Depuis, le Roi me mena dans son voyage avec lui jusques à Calmar, où il arriver, et me mit à une petite épreuve, qui augmenta fort son amitié pour moi. Je n'avois pas encore deux ans quand il arriva à Calmar. On douta s'il falloit faire les salves de la garnison et des canons de la Forteresse pour le saluer selon la coutume, à cause que l'on craignoit de faire peur à un Enfant de l'importance dont j'étois; et pour ne manquer en rien, le Gouverneur de la Place lui demanda l'ordre. Le Roi, après avoir balancé un peu, dit faites, tirez; elle est fille d'un soldat, il faut qu'elle s'y accoutume. Cela fut fait, on fit la salve dans les formes. J'étois avec la Reine dans son carosse, et au-lieu d'un être épouvantée, comme sont les autres enfans à un âge si tendre, je riois et battois des mains; et ne sachant pas encore parler, je témoignois, comme je pouvois, ma joye par toutes les marques que pouvoit donner un enfant de mon âge, ordonnant à ma mode qu'on tirât encore davantage. Cette petite rencontre augmenta beaucoup la tendresse du Roi pour moi; car il espéra que j'étois née intrépide comme lui. Depuis, il me menoit toujours avec lui pour voir ses revues quand il les faisoit de ses troupes, et par-tout je lui donnois des marques de courage, telles qu'en un âge si tendre il pouvoit exiger d'un Enfant qui ne parloit encore qu'avec peine. Il prenoit plaisir à badiner avec moi, il me disoit: Allez, laissez-moi faire: je vous menerai un jour en des lieux où vous aurez contentement. Mais pour mon malheur la mort l'empêcha de me tenir parole, et je n'eus pas le bonheur de faire mon apprentissage sous un si bon Maître."

"Then the King took me with him on his trip to Kalmar. Upon arrival, he subjected me to a little test which greatly strengthened his love for me. I was not yet two years old when we went to Kalmar. One man was hesitant about shooting the salute from the garrison and from the cannons at the castle to greet him in the usual way, as he was afraid of frightening a child as important as I was. To make no mistake, the governor asked for the orders. After thinking, the King answered: 'Go on, shoot. She is the daughter of a soldier and she must get used to it.' I was with the Queen in her carriage, and instead of being frightened like any other child, I laughed and clapped my hands; not being able as yet to speak, I expressed my joy as well as I could in my fashion, gesturing that they should fire again. This little event increased the King's tenderness for me; he hoped I was born as intrepid as himself. Since then, he always took me with him to review the troops, and everywhere I gave him marks of courage, such that at such a tender age he could expect from a child who did not yet speak and still with difficulty. He took pleasure in playing with me, he said to me: 'Someday I will take you to a place that will delight you.' But, to my misfortune, death prevented him from keeping his word, and I never had the good fortune to study under such a good master."

"Quand il partit, j'étois un peu plus grande, et on m'avoit appris un petit compliment qui je devois lui réciter; mais comme il étoit si occupé qu'il ne pouvoit s'amuser à moi, voyant qu'il ne me donnoit pas audience, je le tirai par son buffle et le fis tourner vers moi. Quand il m'apperçut, il me prit entre ses bras et m'embrassa, et ne put retenir ses larmes, à ce que m'ont dit les personnes qui s'y trouverent présentes. Ils m'ont assuré aussi que lorsqu'il partit, je pleurai si fort durant trois jours entiers sans interruption, que cela me causa un si grand mal d'yeux, que je faillis d'en perdre la vue que j'avois extrêmement foible, aussi-bien que le Roi mon Pere. On prit mes larmes pour de mauvais augures, d'autant plus que naturellement je pleurois peu et rarement."

"When he left, I was a little older, and I was taught a little compliment to recite to him; but he was so busy that he did not notice me. Seeing that he was not giving me his attention, I pulled on his buffcoat and made him turn towards me. When he saw me, he took me in his arms and kissed me, and could not restrain his tears, as I was told by the people who were present. They also told me that when he left, I cried so hard for three whole days without stopping that it caused me problems with my eyes, and I almost lost my eyesight, which was very weak as well as that of the King, my father. My tears were taken as a bad omen, especially since I usually cried little and rarely." - Kristina in her autobiography, published by Johan Arckenholtz in 1759

"Gnedigster hertz vilgeliebter herr vatter, E. K. M. sein mein gehorsamen kindtlichen dinst mitt wůnschen von gott dem allmechtigen viller gesünder zeit, mich als eoro getrewe dochter zü trost. Bitte E. M. wollen bald wider kommen und mir aüch waß hubsches sicken, ich bin gott Lob gesündt undt befleijße mich im betten wil alzeit wacker lernen."

"Gracious and beloved Father, Your Royal Majesty has my obedient filial service with the wish that God the Almighty will bring you much good health for the consolation of his obedient daughter. I beg Your Majesty to come back soon and send me something pretty as well. I am, thank God, in good health and I learn to pray always well."

"Gnedigster hertz liber herr vatter Weil ich daß glück nicht hab itz beij E K M. zv seyn so sick ich E M ich mein demütige Conterfeij bitt E M wolle meiner dabeij gedencke vndt balt zv mir wider kommen, mich vnter weil waß hübses sicken. ich wil alzeit from sein vndt fleijsig betten lernen. gott lob ich bin gesundt gott gebe vns alzeit güte zeitung von E M dem selbige befelle E M alzeit."

"Honoured and beloved Father. As I have not the happiness of being with Your Royal Highness, I am sending you my portrait. Please think of me when you look at it, and come back to me soon and send me something pretty in the meantime. I am in good health, thanks be to God, and learn my lessons well. I pray God will send us good news of Your Majesty, and I commend you to His protection." - two letters Kristina wrote to Gustav Adolf sometime in 1631 and probably also 1632

Above: Tre Kronor Castle, built in the 13th century and destroyed by a fire in 1697. The present-day Swedish royal palace, Stockholm Palace, was later built on the site in the 18th century.

Above: Kristina's parents, King Gustav II Adolf and Princess Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg.

Above: Kristina as a toddler, late 1620s.

Above: Kristina at age five, year 1632.

Above: An engraving of the child Kristina in a mourning veil, made in around 1633.

Even as a child, Kristina was said to have a sense of majesty that amazed everyone who was presented to her, and she sat through ceremonies as calmly and stoically as an adult would have, although she later wrote that she was too young at the time to really be able to understand the significance of what was happening. But because the young monarch was underage, a regency was needed to rule in her place until Kristina became old enough to rule, and Gustav Adolf had appointed five men for this job: Grand Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, (who instructed Kristina in politics and statecraft), Grand Treasurer Gabriel Bengtsson Oxenstierna, Grand Marshall Count Jakob de la Gardie, Grand Admiral Carl Carlsson Gyllenhielm, and Grand Steward Gabriel Gustavsson Oxenstierna. Johannes Matthiæ Gothus instructed Kristina in theology, philosophy and Latin.

Above: Tre Kronor Castle, built in the 13th century and destroyed by a fire in 1697. The present-day Swedish royal palace, Stockholm Palace, was later built on the site in the 18th century.

Above: Kristina as a toddler, late 1620s.

Above: Kristina at age five, year 1632.

Above: An engraving of the child Kristina in a mourning veil, made in around 1633.

Even as a child, Kristina was said to have a sense of majesty that amazed everyone who was presented to her, and she sat through ceremonies as calmly and stoically as an adult would have, although she later wrote that she was too young at the time to really be able to understand the significance of what was happening. But because the young monarch was underage, a regency was needed to rule in her place until Kristina became old enough to rule, and Gustav Adolf had appointed five men for this job: Grand Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, (who instructed Kristina in politics and statecraft), Grand Treasurer Gabriel Bengtsson Oxenstierna, Grand Marshall Count Jakob de la Gardie, Grand Admiral Carl Carlsson Gyllenhielm, and Grand Steward Gabriel Gustavsson Oxenstierna. Johannes Matthiæ Gothus instructed Kristina in theology, philosophy and Latin.

"Il faut que je me plaigne ici de la négligence de ma Nation & des Auteurs qui ont écrit cette histoire, qui n'en disent pas un mot. Je ne puis tirer aucune lumière d'eux pour en parler juste, & ma mémoire ne m'en fournit pas aussi. La négligence des Auteurs qui ont écrit, est si grande, qu'ils n'ont pas même daigné remarquer le jour funeste de la mort d'un si grand Roi, ni de mon avénement à la Couronne, qui fut le même dans lequel il mourut. Mais je sais de science certaine, nonobstant une si terrible nonchalance, que ce fut le 16 de Novembre, jour à jamais mémorable à la Suède. Mais je ne sais au vrai quand cette funeste nouvelle arriva en Suède. Je sais pourtant qu'elle arriver par un Extraordinaire, qui avec tout le flegme de la Nation, et le retardement de la saison et des autres accidens, n'y aura mis que peu de jours apparemment. Il faut supposer, qu'on tint la nouvelle secrette dans le Sénate, jusques à ce qu'on eut loisir de délibérer sur tout ce qu'il y avoit à faire dans une si funeste occasion. On m'a voulu persuader, qu'on mit en délibération dans certaines assemblées particulieres, s'il falloit se mettre en liberté, n'ayant qu'un enfant en tête, dont il étoit aisé de se défaire et de s'ériger en République. Mais dans le Sénat on parla un autre langage. Tout le monde opina en ma faveur, et tous conclurent que mon droit étoit incontestable: qu'il falloit observer le serment qu'on m'avoit prêté de la future succession. On se crut encore trop heureux d'avoir cet enfant, qui étoit leur unique ressource et l'unique espérance du salut public de la Suède, dans une conjoncture si dangereuse, si importante et si délicate. C'étoit, disoient-ils, l'unique lien de leur union présente et la seule espérance de leur futur bonheur. On résolut unanimement de me proclamer ce que vous m'aviez fait naître, Reine de Suède, et on ie fit sans tarder un instant, avec les cérémonies accoutumées, et tout le monde alla me reconnoîter. Le Prince Palatin, Beaufrere du Roi, quoiqui'Etranger, fut entre les premiers à faire son devoir, à se ranger auprès de moi et à m'offrir ses services, et tout le monde alla en foule me rendre leurs devoirs. Aussi-tôt on convoqua les Etats généraux en mon nom. On envoya les lettres circulaires à tous les Gouverneurs des Provinces, et on donna tous les ordres nécessaires pour ma sureté et pour celle du Royaume. On me fit prendre le deuil avec toute la Cour et la Ville, et on n'omit rien de tout ce qui se doit faire en de semblables occasions. J'étois si enfant, que je ne connoissois ni mon malheur, ni ma fortune: mais je me souviens pourtant, que j'étois ravie de voir ces gens à mes pieds me baiser la main."

"I must complain here about the negligence of my nation and the authors who wrote this story, who do not say a word about it. I cannot draw any light from them to merely talk about it, and my memory does not provide me with it either. The negligence of the authors who have written is so great that they have not even deigned to notice the fatal day of the death of so great a King, nor of my accession to the Crown, which was the same day on which he died. But I know with certainty, notwithstanding such terrible nonchalance, that it was the 16th of November, a day forever memorable to Sweden. But I do not know the truth of when this fatal news arrived in Sweden. I do know, however, that it arrived by a courrier, who, with all the phlegm of the nation, and the delay of the season and other accidents, had taken but a few days, apparently. One can assume that the news was kept secret in the council until it had overtaken all the actions required in such a serious event. I have been told that it was debated in certain particular assemblies whether it was necessary to liberate themselves, having only a child at the helm, who would be easy to get rid of, and then set up a republic. But in the Senate another language was spoken. Everyone opted in my favour, and all concluded that my right was incontestable, that it was necessary to observe the oath that had been taken to me from the future succession. They thought themselves still too fortunate to have this child, who was their only resource and the only hope for the public safety of Sweden, in a situation so dangerous, so important, and so delicate. It was, they said, the only link between their present union and the only hope of their future happiness. It was unanimously resolved to proclaim me as what You had made me: Queen of Sweden; and it was promptly done, with the usual ceremonies, and everyone went to honour me. The Count Palatine, the King's brother-in-law, though a foreigner, was among the first to do his duty, to come up to me and to offer me his service, and everybody went in crowds to pay me their respects. Immediately thereafter, the Estates of the Realm convened in my name. Letters were sent to all the governors of the provinces, and all the necessary orders were given for my safety and that of the kingdom. They had me mourn with the whole Court and the city, and neglected nothing about everything that should be done on such occasions. I was such a child that I did not comprehend either my misfortune or my fortune; but I do remember that I was delighted to see all these people at my feet kissing my hand."

"Lorsque les Etats se trouverent assemblés, il falloit monter sur un Trône, dont je ne connoissois ni les devoirs, ni les charges. Je ne connoissois pas encore à quoi m'obligeoit un si terrible poste. J'ignorois combien il faloit veiller, suer, et travailler pour s'en rendre digne, et le terrible compte que je devois, Seigneur, vous rendre de l'avoir mal rempli. Je n'avois pas l'esprit de vous rendre l'hommage que je vous devois, ni d'implorer votre secours dans un si pressant besoin. Ce fut vous, Seigneur, qui rendîtes alors un enfant admirable à son peuple, qui s'étonna de la grande maniere avec laquelle je saisois déjà la Reine en cette premiere occasion. J'étois petite, mais j'avois sur le Trône un air et une mine si grande, qu'elle inspiroit le respect et la crainte à tout le monde. C'est vous, Seigneur, qui saisiez paroître telle une fille qui n'avoit pas encore l'usage de la raison. Vous aviez imprimé sur mon front cette marque de grandeur, que vous ne donnez pas à tons ceux que vous avez destinés, comme moi, à la gloire d'être votre Lieutenant entre les hommes. On disoit: comment est-il possible, qu'un enfant nous inspire de tels sentimens après avoir vu un Trône rempli de Gustave le Grand? On remarqua, que vous m'aviez rendue si grave et si sérieuse, que je ne témoignois aucune impatience d'enfant: que je ne m'endormois pas durant de si longues cérémonies, et tant de harangues, qu'il me falloit essuyer. On en a vu souvent d'autres s'endormir ou pleurer à chaudes larmes en de semblables occasions, mais on me vit recevoir tous les hommages avec un air d'une personne âgée, qui connoit qu'ils lui sont dûs. Il faut si peu de chose pour faire admirer un enfant, mais de plus un enfant du Grand Gustave: et peut être que la flatterie qui nait et meurt avec nous, en a aussi exagéré tout ce qu'on m'en a dit. Je sais pourtant que vous pouvez tout, et que vous avez fait d'autres miracles et ma faveur. Je me souviens encore trop bien d'avoir entendu dire tout cela, et que j'en eus une complaisance qui me rendit des-lors criminelle envers vous, en me rendant très contente de moi-même, m'imaginant que j'avois fait merveille, et que j'étois déjà fort habile, ne connoissant pas encore que je devois tout à votre seule bonté, non plus que les terribles obligations de mon devoir."

"When the statesmen were assembled, it was necessary of me to sit on the Throne, of which I knew neither the duties nor the charges. I did not yet know what was the purpose of such a tremendous job. I did not know how much one had to be vigilant, sweat, and work to make oneself worthy of it, and the dreadful account that I would have owed you, Lord, if I had filled that role badly. I did not mind to pay You the homage I owe You, nor to implore Your help in so urgent a need. It was You, Lord, who made an admirable child for those people, who were astonished at the great manner in which I already knew my role as Queen on this first occasion. I was little, but on the throne I had an air and a mien so great that it inspired respect and fear in everyone. It was You, Lord, who took such a girl who did not yet have the use of reason. You had planted on my forehead this mark of greatness, which You only give to all those who You have destined, like me, to the glory of being Your intermediary between men. It was wondered: 'How is it possible that a child inspires such feelings in us after we have seen a throne sat upon by Gustav the Great?' It was noticed that You had made me so grave and so serious, in fact, that I showed no childish impatience. I never fell asleep during all the long ceremonies and speeches I had to sit through. Other children have been seen falling asleep or crying on occasions like this, but I received all the different signs of homage like a grownup who knows they are his due. It takes so little to admire a child, but moreover a child of the great Gustav, and perhaps the flattery which is born and dies with us has also exaggerated all that was said to me. I know, however, that You can do everything, and that You have done other miracles and my favour. I still remember too well having heard all this, and that I had a complacency that made me a criminal at times in Your eyes, being very content with myself, imagining that I had done miracles, and that I was already very skilful, not yet knowing that I owed everything to You alone, no more than the terrible obligations of my duty." - Kristina in her autobiography, published by Johan Arckenholtz in 1759.

"Axell Baner och Erich Ryningh ähre alt hooss vår unge Dråttningh i Nyköpingh och agta på H. M:tt, tillseendes om hennes education, och Magister Johannes Mattiæ informerar henne; haffuer ett extra ordinarij ståteliget ingenium, men conversatio cum matre ähr myckett skadeligh."

"Axel Banér and Erik Ryning are with our young Queen in Nyköping and taking care of her education, and Master Johannes Matthiæ is teaching her; she has an extraordinary stately intelligence, but her conversation with her mother is very harmful." - High Steward Gabriel Gustafsson Oxenstierna in his letter to Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, dated December 27, 1633

"H. M:t unge drotningen ähr vedh helsan och uptuktes i alla kongelige dygder så mycket möijligit ähr och hennes unge åhr kunne medhgiffva. H. M:t haffver mycket aff sina högtberömde förfäders the höglofflige konungars bloodh och gemuth, ähr flitigh, generos, efftertencksam och uthi sitt taal mycket gratios, så att om H. M:t en godh hopning ähr att hon uthi sina förfäders footspår visserligen träda skall, så frampt Gudh henne lijffvet unnar, det iagh innerligen vill önskat haffva."

"Her Majesty the young Queen is healthy and is instructed in all royal virtues as much as possible, and her youthful age can agree. Her Majesty has much of the blood and courage of her famous forefathers, the highly honourable kings, is diligent, generous, thoughtful and very gracious in her speech, so there is a good hope for Her Majesty that she shall surely follow in her forefathers' footsteps, so long as God lets her live, for which I dearly wish." - Count Johan Oxenstierna in his letter to Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, dated February 13, 1636

Above: Axel Oxenstierna.

Although Gustav Adolf had ordered for his half-sister, Princess Katarina (1584-1638) to have custody of Kristina in the event of his death, as he did not feel that Maria Eleonora, who had been excluded from the regency, was emotionally stable enough to raise Kristina, Kristina was made to live at Nyköping Castle with and by her grieving mother. Maria Eleonora had once resented Kristina, but now she became obsessed with the child, citing Kristina's resemblance to the late king.

Above: Axel Oxenstierna.

Although Gustav Adolf had ordered for his half-sister, Princess Katarina (1584-1638) to have custody of Kristina in the event of his death, as he did not feel that Maria Eleonora, who had been excluded from the regency, was emotionally stable enough to raise Kristina, Kristina was made to live at Nyköping Castle with and by her grieving mother. Maria Eleonora had once resented Kristina, but now she became obsessed with the child, citing Kristina's resemblance to the late king.

Maria Eleonora would become depressed and desperate during her husband's absences, but now that she had lost him, she became literally insane from grief. Her apartments in the castle were draped with black velvet, surrounding herself and little Kristina in constant darkness. Maria Eleonora ordered that Gustav Adolf's body not be buried until her own death; she visited his body often and talked to and even touched it despite the putrefaction, and she kept his heart in its own little casket which she hung above the bed she forced Kristina to sleep in with her, and the child was of course overwhelmed by her mother's constant loud wailing and the general atmosphere of the situation. Maria Eleonora surrounded herself with dwarves and hunchbacks for entertainment, and Kristina was terrified of them as a child and disgusted at them as an adult. This was probably the result of or contribution to her self-consciousness of her own body and deformities. Kristina was rarely let out of her mother's sight, and she used her daily lessons as a way to escape from her.

Axel Oxenstierna and the other councilmen were deeply disturbed by all this and wanted to save Kristina, but Maria Eleonora's tearful protests rendered them powerless to take the child away. Gustav Adolf's body was not buried until eighteen months after his death; and in August 1636, Maria Eleonora's parental rights were stripped and she was exiled to Gripsholm Castle while the 9½ year old Kristina was taken to live with her aunt Princess Katarina and her family in their home at Stegeborg Castle.

Maria Eleonora's vanity and hyperfemininity had a lasting and negative effect on Kristina's view of women, which we will see further examples of later. Her behaviour and ideals also left Kristina with a deep dislike of Germany and all things German, deep enough to rival Maria Eleonora's own dislike of Sweden, and Kristina as an adult often and bluntly expressed her dislike of Germany in letters to Cardinal Decio Azzolino during her stay in Hamburg from 1666 to 1668, seeing the German people as just as strange and barbarous as the ancient Romans viewed them when they were tribes.

After Katarina's death in December 1638, Kristina was given a rotation of four foster mothers: Ebba Leijonhufvud, Kirstin Natt och Dag, Beata Oxenstierna and Ebba Ryning. This was done in an attempt to ensure that the young monarch would not become too attached to any one favourite mother figure, and it appears to have succeeded.

"... Les Muscovites envoyérent une Ambassade solemnelle pour faire leurs complimens de congratulation & de condoléance, & pour demander en même tems la ratification de la paix faite en 1617 avec le feu Roi. Ils m'apportérent de magnifiques présens selon la coutume. On leur répondit de ma part dans les formes. Ils eurent ce qu'ils demandérent, & furent dépêchés avec les présens accoutumés. Cette Ambassade arriva à Nykoping, où j'étois allée recevoir la Reine, ma Mere, qui débarqua en cette ville avec le cadavre du seu Roi. ... J'étois si fort enfant, qu'on craignoit que je ne pusse soutenir cette Ambassade avec la gravité qu'il faloit. On craignoit qu'elle me seroit peur avec les manières et habits barbares, qui m'étoient encore inconnus. On me fit donc une grande préparation là-dessus. On m'instruisit de tout le Cérémonial, & on m'exhorta à n'avoir pas peur. Ce doute me piqua fort, & je demandois toute en colère, pourquoi aurois-je peur? On me dit que les Muscovites étoient des gens habillés tout autrement que nous: qu'ils avoient de grandes barbes: qu'ils étoient terribles: qu'ils étoient un grand nombres: mais qu'il ne falloit pas en avoir peur. Par hazard ceux qui étoient mes Confortateurs en cette occasion, étoient le Grand-Connétable & le Grand-Amiral, qui eux-mêmes avoient de grandes barbes: ce qui me fit dire là-dessus en riant: que m'importe leurs barbes? Vous autres n'avez-vous pas la barbe grande? & je ne vous crains pas: & pourquoi me seront-ils peur? Instruisez-moi bien, & laissez-moi faire. En effet je leur tins parole. Je donnai l'audience sur le Trône, selon la coutume, avec une mine si assurée & si majestueuse, qu'au-lieu d'avoir peur, comme il est arrivé à d'autres enfans en semblables occasions, je fis sentir aux Ambassadeurs ce que ressentent tous les hommes, quand ils approchent de tout ce qui est le plus grand, & je ravis de joye les miens, qui m'admirérent, comme on sait ordinairement sur toutes les bagatelles des enfans qu'on aime."

"The Muscovites sent a solemn embassy to congratulate and condole me, and at the same time to request from me the ratification of the peace made in 1617 with the King. They brought me magnificent presents according to custom. They were answered on my behalf in the usual forms. They got what they asked for, and were dispatched with the customary presents. This embassy arrived at Nyköping, where I had gone to receive the Queen my mother, who landed in that city with the body of the King. ... I was such a child that it was feared that I could not receive this embassy with the necessary gravitas. It was feared that I would be afraid of them with their barbarous manners and clothes, which were still unknown to me. So I was given a lot of preparation on that. I was instructed in all the ceremonials, and they exhorted me not to be afraid. This doubt piqued me very much, and I asked in anger: 'Why should I be afraid?' I was told that the Muscovites were people dressed quite differently from us, that they had large beards, that they were terrible, that there was a great number of them; but that I mustn't be afraid of them. By chance, those who were my comforters on this occasion were the Grand Marshall and the Grand Admiral, who themselves had large beards, which made me say with a laugh: 'What do I care about their beards? Do you not have large beards? And I am not afraid of you, so why should I be afraid of them? Just tell me what to do and leave it all to me.' Indeed, I gave them my word. I gave the audience on the throne, according to custom, with a mien so assured and so majestic that, instead of me being afraid, as has happened to other children on similar occasions, I made the ambassadors feel what all men feel when they approach that which is greater than themselves, and I delighted my courtiers, who admired me, as is the usual reception of all the trifles of the children we love." - Kristina in her autobiography, published by Johan Arckenholtz in 1759. The Muscovite embassy arrived in Nyköping on August 6, 1633.

"Presqu'en même tems la Reine, ma Mére, arriva. Elle fut reçuë dans les formes. J'allai en personne à sa rencontre avec tout le Sénat & toute la Noblesse de l'un & de l'autre Sexe de la Cour. Les larmes & les pleurs se renouvellérent à ce triste spectacle. J'embrassai la Reine, ma Mére. Elle me noya dans ses larmes, & pensa presque m'étouffer entre ses bras. On mit en dépôt le cadavre du Roi dans le Château. On fit toutes les cérémonies selon la mode du païs pour honorer la mémoire du plus grand Roi qui eût jamais régné en Suède. On me fit essuyer quantité de sermons & de harangues, qui m'étoient plus insupportables que la mort du Roi, mon Pére, dont j'étois toute consolée, il y avoit longtems, ne connoissant pas mon malheur. Mais je crains fort que je m'en fusse consolée plutôt, si j'eusse été en état de le connoître. Car les enfans qui attendent la Succession d'une Couronne, se consolent aisément de la perte d'un Pére. Mais toutefois le mien étoit si aimable, & je l'aimois si fort, que je pense que ma fortune ne m'auroit pas trop consolée de mon malheur, si j'eusse été capable de le connoître. Mais quoi qu'il en soit, il y avoit presque deux ans qu'il étoit mort, & je m'ennuyois furieusement de ces longues & tristes cérémonies. Mais ce qui acheva de me désoler, fut la vie lugubre que menoit la Reine-Mére. D'abord qu'elle fut arrivée, elle se renferma dans son appartement, qui étoit tout couvert de drap noir depuis le plat-fond jusqu'au pavé. Les fenêtres de cet appartement étoient fermées d'une étoffe de la même couleur. On n'y voyoit goutte, & on y brûloit jour & nuit des flambeaux de cire, qui ne faisoient voir que les tristes objets d'un deuil. Elle pleuroit presque jour & nuit, & il y avoit des jours qu'elle renforçoit ses douleurs d'une si étrange maniére, qu'elle faisoit pitié. J'avois pour elle un grand respect & une assez tendre amour. Mais ce respect me gênoit & me devint incommode, sur-tout quand elle s'empara malgré mes Tuteurs de ma personne, & qu'elle vouloit m'enfermer avec elles dans son appartement. Elle commença d'abord à blâmer l'éducation qu'on m'avoit donnée jusqu'alors. Elle eut même quelque démêlé avec la Régence là-dessus. Mais le respect qu'on avoit pour elle, fit qu'on lui donna quelque liberté là-dessus pour quelque tems. On lui permit de me gouverner à sa mode, puisqu'on lui avoit ôté la Régence. On crut lui devoir cette indulgence pour le reste. Cela fit qu'elle éloigna aussi ma Tante d'auprès de moi, disant qu'elle vouloit être elle-même ma Gouvernante. Elle tenta d'autres changemens aussi, mais on s'y opposa avec raison. Cependant elle m'aimoit tendrement, d'autant plus qu'elle disoit que j'étois la vivante image du feu Roi. Mais à force de m'aimer, elle me fit désespérer. Elle me faisoit coucher avec elle, & ne me perdoit presque pas de vue. Ce fut avec peine que je pouvois obtenir permission d'aller étudier dans mon appartement, & d'y faire mes exercices."

"Almost at the same time, the Queen, my mother, arrived. She was received according to all accepted forms. I had to meet her in person with the whole Council and all the court nobles of both sexes. The tears and weeping gained new momentum at this sad spectacle. I embraced the Queen my mother, she drowned me in tears and almost suffocated me in her arms. The King's body was kept in the castle, and all the solemn ceremonies prescribed by the country's customs were performed to honour the memory of the greatest king who ever ruled in Sweden. I had to endure an endless number of speeches and sermons that were harder for me to endure than the fact that the King, my father, was dead. I had long before gotten over that, because I did not understand the extent of my misfortune. I strongly doubt that I would have been comforted as soon as I had been old enough to understand my grief. Children waiting to inherit a royal crown are easily comforted when they lose their father. But my father was so amiable and I loved him so much that I do not think that happiness could have overshadowed the misfortune, if I had been able to grasp it. Be that as it may, he had been dead for almost two years, and I was terribly sad during these long and sad ceremonies. But most deplorable of all was the lugubrious life that the Dowager Queen led. As soon as she arrived, she locked herself in her apartment, which was completely covered with black cloth from floor to ceiling. In front of the windows on the floor hung fabric of the same color. One could not see a thing, and through the days and nights torches burned with wax whose light was so faint that one could not discern anything but the objects of mourning. She wept almost all day and all night, and on some days her pain increased in such a strange way that one must feel sorry for her. I had great respect for her and loved her quite tenderly. But this reverence afflicted me, and it disturbed me, especially when, against the will of my guardians, she took me with her and tried to keep me locked up in her apartment. At first she began to complain about the upbringing I had received so far. She even came into conflict with the regency government over the matter. Out of respect for her, she was given some freedom in that regard for a time. She was allowed to control me as she wished because she had been kept out of the guardianship. It was thought that she was owed this concession in other matters. As a result, she separated me from my aunt because, as she said, she would be my governess herself. She also tried to enforce other changes that were rightly opposed. However, she loved me tenderly, especially as she said I was a living image of the late King. But by dint of loving me she made me despair. She forced me to sleep next to her, and she never let me out of sight. She barely allowed me to go to my own rooms to read and do my studies."

"On voulut alors me séparer d'appartement d'avec la Reine, ma Mére; mais quand on lui en fit la proposition, c'étoient des pleurs & des cris qui faisoient pitié à tout le monde. Cela embarrassoit fort la Régence, qui lui fit souvent des remontrances là-dessus. Mais on n'en vint jamais à bout, jusques à ce que le Grand-Chancelier Oxenstierna fût arrivé. On délibéra souvent au Sénat sur cette affaire. On fit plusieurs remontrances à la Reine-Mére. On m'en fit à moi, qui ne souhaittois rien plus que de m'en éloigner, quoiqu'elle me fit pitié dans le déplaisir qu'elle en témoignoit, & que je l'aimois tendrement. J'avois une espéce de respect pour elle, qui me gênoit fort, & je craignois qu'elle ne fût d'un grand obstacle dans mes études & mes exercices: ce qui me fâchoit fort, car j'avois un extrême desir d'apprendre. En outre, la Reine-Mére se plaîsoit à entretenir un nombre de bouffons & de nains, dont son appartement étoit toujours rempli à la mode d'Allemagne: ce qui m'étoit insupportable, car j'ai naturellement une aversion mortelle pour ces sortes de canailles. Aussi j'étois ravie quand mes heures d'études m'appelloient dans mon appartement. Je ne me faisois pas solliciter. J'y allois avec une joye inconcevable, & j'avançois même les heures de m'y rendre. J'étudiai six heures le matin & autant le soir. Les samedis & les fêtes étoient vacance pour moi, dans lesquels je passois mon tems comme je l'ai déjà dit."

"They also wanted me to live apart from my mother, the Queen, but when this was suggested to her, she let out so much crying and screaming that it aroused pity in everyone. This displeased my guardians, who often gave her a sharp reprimand for this. But they never truly got over it until Chancellor Oxenstierna came home. The matter was often the subject of discussion in the Council. Attempts were made several times to speak to the Dowager Queen. They also talked to me, who wanted nothing more than to leave her, even though I loved her tenderly and felt sorry for her because she was upset about it all. I had a type of respect for her that bothered me greatly, and I was afraid that she would stand in the way of my studies and exercises. This irritated me, because my thirst for knowledge was so great. Moreover, the Dowager Queen enjoyed keeping a number of buffoons and dwarves, who in the German way always filled her apartment. I found them unbearable, because I have always hated those kinds of scum. Therefore I was happy when it was time for me to go to my own apartment to study. One did not have to get after me, I was indescribably happy when I went there, and I even went earlier than necessary. I spent six hours in the morning studying and just as much in the evening. On Saturdays and weekends I was free, and then I spent the time as I have told before." - Kristina in her autobiography, published by Johan Arckenholtz in 1759.

"Jag önskar Eders fürsteliga nåde mycken wälsignelse af Gudi, och tackar E. F. N. för al then höga omwårdnad och stora affection E. F. N. härtil för mig dragit, synnerlig för thet E. F. N. mig med sina wänliga skrifwelser åtskilliga gångor besökt hafwer. Jag lefwer uti then goda förhopning, E. F. N. skal och härefter sin goda wändskap emot mig continuera och beholla: lofwar mig däremot altid wela temoignera en sådan benägenhet emot E. F. N. samt E. F. N. älskelige K. Gemåhl och hela Famillen."

"I wish Your Highness many blessings from God, and I thank Your Highness for all the concern and great affection you have shown me, especially for that Your Highness has honored me many times with your kind letters. I live in the good hope that you will continue and preserve your friendship toward me, I in turn promise to always show my gratitude to the person of Your Serene Highness as well as to your husband and entire family." - Kristina in a letter to her aunt Princess Katarina, dated April 19, 1634

"Ett moste jagh mentionera, dett jagh inthe gerna gör. ... H. M:tt Enckiedråttningen bliffuer myckett oroligh; impedierar mycket vår unga Frökens institution, informerar henne till all vedervertighet och haat emot våre personer och nation, tillsteder ingen aga, lährer löpa om medh fåfengt snack som andra. Hooss Fru Moderen geller inge förmaningar. ... Synes altså, att dotter och moder moste skilias åht."

"I must mention one thing, I do not do it gladly. ... Her Majesty the Dowager Queen is very restless, greatly impedes our young Lady's education, informs her in all misery and hate against our persons and nation, there is no discipline, she lets her go around with idle talk like others. There are no admonitions from her Lady Mother. ... It therefore seems that the daughter and mother must be separated." - Grand Steward Gabriel Gustafsson Oxenstierna in his letter to Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, dated March 20, 1635

"Inthet kan iagh mehra säija ähn att vår allernådigste uthkorade unge drotning ähr vedh helsan och mår temligh väl. Enkiedrotningenh ähr eder K. Herfader något oblijdh. Orsaken veet icke iagh och iagh troor inthet att hon sielf rätt väl veet henne."

"I can say nothing more except that our most gracious young Queen-elect is healthy and faring reasonably well. The Dowager Queen is somewhat displeased with you, dear Father. I do not know the reason and I do not think she herself knows well why." - Count Johan Oxenstierna in his letter to Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, dated April 30, 1636

"She took her model of all women from her mother, and declared that, of all human defects, to be a woman was the worst." - from Christina, Queen of Sweden: The Restless Life of a European Eccentric (2004), by Veronica Buckley

"She took her model of all women from her mother, and declared that, of all human defects, to be a woman was the worst." - from Christina, Queen of Sweden: The Restless Life of a European Eccentric (2004), by Veronica Buckley

"Jagh skulle ... haffva varit hemma bijvistats min svärmoder och henne uthi sine private saker assisterat, alt till den ände att jagh effter Min K. Herfaders commission och begäran skulle henne persuadera till att taga sigh H. K. M:ts min unge drotnings upfödzel upå, så vida hon det kan göra."

"I should ... have been home with my mother-in-law and assisted her in her private affairs, all to the end that I, after my dear Father's commission and request, should persuade her to take up, as well as she can, the upbringing of Her Royal Majesty my young Queen." - Count Johan Oxenstierna in his letter to Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, dated January 10, 1639

"Ich kan Ew[er] L[iebden] nicht genugsam die grose treu und dienste vergelten, so Ew[er] L[iebden] seelige in Gott ruhende hertzliebe Gemahlin mir bewiesen hat, als eine rechte Vater-Schwester: nicht dass ich sage allein Vater-Schwester, sondern als eine natürliche Mutter."

"I cannot give Your Lovingness enough to reward the great loyalty and service that Your Lovingness's dearly beloved wife has proven to me, resting in God, as a true aunt; not only as an aunt, but as a natural mother." - Kristina in a letter to her uncle Count Palatine Johan Kasimir, dated February 25, 1639

"Jam jam venit Magistra aulæ Domina Beata Oxenstierna & Ejus filia. Quò plures, eò peius."

"The Grand Mistress of the Court, Lady Beata Oxenstierna and her daughter are arriving in the moment. The more of them that come, the worse it is." - Kristina in a letter to her uncle Count Palatine Johan Kasimir, dated June 28, 1639

"Apres avoir heureusement traverse la deserte, puante et barbare Allemange ie suis enfin arive icy hier au soir icy et iay receu auec Joye vos lettres vn iour devan que dy arriver."

"After having happily crossed the deserted, stinking and barbarous Germany, I finally arrived here yesterday evening and received your letters joyfully one day before arriving there." - Kristina in a letter to Cardinal Decio Azzolino, dated June 23, 1666

"Jl Courent ysy des livres infames et sots Contre la Cour de rome, et la Vie de D. Olimpia est receue avec tan dapplaudissements qvelle est tradiuitte en touts les langes barvares cest le plus sot livre dv monde, et a moin qve destre Hretique ov allemant lon ne sauroit trouver plaisir au sotises quil dit. enCore Vaut Jl mieux destre Héretiqve qu'Aleman car enfin vn heretiqve peut devenir Catolique mais vne beste ne peut iamais devenir raisonable. maudit soit le pays et les sotte bestes quil produit."

"They are circulating here infamous and foolish books against the Court of Rome, and the life of Donna Olimpia is received with so much applause that it is translated into all barbaric languages. It is the stupidest book in the world, and unless one is heretical or German, one cannot find pleasure in the nonsense it says. Still better to be a heretic than German, for in the end a heretic can become a Catholic, but a beast can never become reasonable. Cursed be this country and the silly beasts it produces!" - Kristina in a letter to Cardinal Decio Azzolino, dated July 28, 1666

"Jl mariva vne plaisante affaire avec vne des sibilliles des ses pays qui par malheur, me trouva avec un livre fransoy a la main. Cela luy donna malheureusement occasion dentre en matiere des livres, et de dire quelle avoit beaucoup leu en sa vie et quelle sen estoit gaste la veu et que cela faisoit qvelle ne lisoit plus puis quelle Craingoit de la perdre. Je luy repodis que ie lisois si peu que ie ne Craingois pas ce malheur, et que iavois gace a dieu la veue raisonablement bonne. elle me dit que Cela nenpechoit pas quelle ne se fust reserve vn seul livre quelle lisoit enCore tous les iours sens y manquer iamais. et Conoissan quelle avoit grande envie que ie luy tesmoingasse de la Curiosite de savoir quel estoit ce livre, ie le fis et la pressay pour le savoir, et apres beaucoup de facons qui me firent qvasi passer lenvie de lapprendre, elle me dit que sestoit le Compendium de la filosofie d'Aristote quelle avoit Chosise pour son vnique livre. Cette reponse me donna la plus forte envie de rire qve ieuse iamais et ie ne say Comment ieuse la force de men empecher. ie luy dis donc quelle avoit tres bien Chosye et quoy que ie ne Conossoit Aristote que de reputation, Je Jay estois prest a le Croire digne delle puil quil avoit lhoneur de luy plaire. Je vous escrits cette Conversation pour vous faire Conoistre le genie des Allemandes quant par malheur on en renContre quelune qui sache quattre mots de latin qui ne sert qua les rendre plus sots que la nature les fait a lordinaire. Juges quel plaisir lon pevt tirer des ces sorte de Conversations."

"A pleasant affair happened to me with one of the Sibylls of this country, who, unfortunately, found me with a French book in hand. This unfortunately gave her the opportunity to get talking about books and to say that she had read a lot in her life, that she had ruined her eyesight, and that this made it so that she no longer read since she feared losing her sight. I replied that I read so little that I did not fear this misfortune, and that I had, thanks to God, reasonably good eyesight. She told me that that didn't prevent her from reserving just one book, which she still reads every day without ever losing her sight. And knowing that she really wanted me to show her my curiosity to know what this book was, I did it, and pressed her to find out, and, after many ways, which almost made me want to do without the need to know, she told me that it was the 'Compendium of Aristotle's Philosophy' that she had chosen as her only book. This response made me want to laugh as much as I ever had, and I don't know how I had the strength to stop myself. So I told her that she had chosen very well and that, although I only knew Aristotle by reputation, I was ready to believe him worthy of her, since he had the honour of pleasing her. I am writing this conversation to let you know the genius of the German women when, unfortunately, one meets someone who knows only four words of Latin, which only serves to make them more stupid than what nature made ordinary. Judge what pleasure one can get from these kinds of conversations!" - Kristina in a letter to Cardinal Decio Azzolino, dated September 23, 1666

Above: The now mostly-ruined Nyköping Castle, where the child Kristina lived with her mother in a nightmare of extreme and excessive mourning. Photo taken by Jacob Truedson Demitz for Ristesson, on Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Maria Eleonora and a lady-in-waiting weeping over the body of Gustav Adolf in this 19th century imagining.

Above: The widowed Maria Eleonora in mourning.

Above: Kristina as a child in mourning for her father.

Above: Gripsholm Castle, where Maria Eleonora lived in internal exile after losing custody of Kristina. Photo taken by Xauxa (Håkan Svensson) at Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Kristina's paternal aunt, Princess Katarina.

Above: Stegeborg Castle, the residence of Princess Katarina and her family, as it appeared years later in 1700. It is now in ruins.

Above: Kristina as a child, painted by Jacob Heinrich Elbfas, mid-1630s.

Above: Kristina, painted by or after the same artist. Here she is probably around twelve years old.

Above: Kristina as a teenager in 1641, also painted by Elbfas.

Above: Young Kristina on a page preceding the texts in a Finnish Bible, year 1642.

Above: Kristina, year 1649.

The regency ruled in Kristina's place until the young monarch came of age in 1644, although her coronation was delayed several times until finally taking place on October 20, 1650 because of the Torstensson War with Denmark. The coronation ceremony took place at Storkyrkan (Stockholm Cathedral), preceded by a procession from Jakobsdal (now Ulriksdal) Palace. Kristina rode in a beautiful carriage draped in black velvet, embroidered in gold and pulled by three white horses. At the ceremony, she was anointed with oil and was presented with the orb, the scepter, and, of course, the crown. To end the ceremony, the harald proclaimed: Nu är drotning Christina Crönter Konung öfuer Swea och Götha Landom och dess Underliggiande Provincier, och ingen annan. Now Queen Kristina is crowned King of the Swede and Goth Lands and their underlying Provinces, and no one else.

Above: The now mostly-ruined Nyköping Castle, where the child Kristina lived with her mother in a nightmare of extreme and excessive mourning. Photo taken by Jacob Truedson Demitz for Ristesson, on Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Maria Eleonora and a lady-in-waiting weeping over the body of Gustav Adolf in this 19th century imagining.

Above: The widowed Maria Eleonora in mourning.

Above: Kristina as a child in mourning for her father.

Above: Gripsholm Castle, where Maria Eleonora lived in internal exile after losing custody of Kristina. Photo taken by Xauxa (Håkan Svensson) at Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Kristina's paternal aunt, Princess Katarina.

Above: Stegeborg Castle, the residence of Princess Katarina and her family, as it appeared years later in 1700. It is now in ruins.

Above: Kristina as a child, painted by Jacob Heinrich Elbfas, mid-1630s.

Above: Kristina, painted by or after the same artist. Here she is probably around twelve years old.

Above: Kristina as a teenager in 1641, also painted by Elbfas.

Above: Young Kristina on a page preceding the texts in a Finnish Bible, year 1642.

Above: Kristina, year 1649.

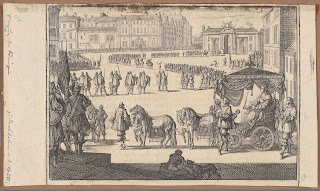

The regency ruled in Kristina's place until the young monarch came of age in 1644, although her coronation was delayed several times until finally taking place on October 20, 1650 because of the Torstensson War with Denmark. The coronation ceremony took place at Storkyrkan (Stockholm Cathedral), preceded by a procession from Jakobsdal (now Ulriksdal) Palace. Kristina rode in a beautiful carriage draped in black velvet, embroidered in gold and pulled by three white horses. At the ceremony, she was anointed with oil and was presented with the orb, the scepter, and, of course, the crown. To end the ceremony, the harald proclaimed: Nu är drotning Christina Crönter Konung öfuer Swea och Götha Landom och dess Underliggiande Provincier, och ingen annan. Now Queen Kristina is crowned King of the Swede and Goth Lands and their underlying Provinces, and no one else.

Kristina's royal motto was Columnia regi sapientia. Wisdom is the realm's support.

In celebration of the event, there was a dinner party at the castle, wine fountains stood in the marketplace for three days, a roast ox filled with various other roast meats was served (it was done again to celebrate Kristina's 25th birthday later that year), and there were illuminations. On October 24, there was a themed parade, Lycksalighetens Ähre-Pracht (The Illustrious Splendours of Felicity).

Above: Kristina as a young adult, circa 1650.

Above: Jakobsdal Palace, now Ulriksdal Palace. Photo taken by Holger.Ellgaard of Wikimedia Commons. The procession for Kristina's coronation began from here.

Above: Kristina's coronation procession.

Above: Storkyrkan, the cathedral in Stockholm where the coronation ceremony took place. Photo taken by Jacob Truedson Demitz for Ristesson, on Wikimedia Commons.

Above: The interior. Photo taken by Zairon at Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Kristina on her coronation day.

Above: The carriage in which Kristina rode to her coronation. Photo courtesy of Livrustkammaren via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: The Silver Throne, made in 1650 for Kristina's coronation by Abraham Drentwett and given as a gift to Kristina by one of her favourites, Count Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie. It is now kept in the Hall of State and was last used in 1975.

Above: Kristina's coronation robe.

Above: A view of Stockholm made by Wolfgang Hartmann in honour of Kristina's coronation.

During her reign, Kristina wanted peace for Sweden at any cost. First, after a few months of peace negotiations, the Treaty of Brömsebro ended the Torstensson War in the summer of 1645; and after a few years of peace negotiations, the Thirty Years' War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia in the autumn of 1648.

In celebration of the event, there was a dinner party at the castle, wine fountains stood in the marketplace for three days, a roast ox filled with various other roast meats was served (it was done again to celebrate Kristina's 25th birthday later that year), and there were illuminations. On October 24, there was a themed parade, Lycksalighetens Ähre-Pracht (The Illustrious Splendours of Felicity).

Above: Kristina as a young adult, circa 1650.

Above: Jakobsdal Palace, now Ulriksdal Palace. Photo taken by Holger.Ellgaard of Wikimedia Commons. The procession for Kristina's coronation began from here.

Above: Kristina's coronation procession.

Above: The interior. Photo taken by Zairon at Wikimedia Commons.

Above: Kristina on her coronation day.

Above: The carriage in which Kristina rode to her coronation. Photo courtesy of Livrustkammaren via Wikimedia Commons.

Above: The Silver Throne, made in 1650 for Kristina's coronation by Abraham Drentwett and given as a gift to Kristina by one of her favourites, Count Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie. It is now kept in the Hall of State and was last used in 1975.

Above: Kristina's coronation robe.

Above: A view of Stockholm made by Wolfgang Hartmann in honour of Kristina's coronation.

During her reign, Kristina wanted peace for Sweden at any cost. First, after a few months of peace negotiations, the Treaty of Brömsebro ended the Torstensson War in the summer of 1645; and after a few years of peace negotiations, the Thirty Years' War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Westphalia in the autumn of 1648.

"Utaff Edere skriwelser hawer Jagh nogsamt wornumit huru wida det med fritztractaten war kommit så wel som Mons de la Tuillery discurser medh eder om Cautionen. Nuh sedermera hawa the danske skridit saken nermare medh Halmstads tilbud. men for nimmer doch att medh seneste post dem intet wilia gripa sig nermare ahn, Medan i nuh vthi ett aff edre skriwelser mena att entligen stanna på halland och bleking skulle fulle wara det säkraste. och moste med Eder bekenna att, med mindre man bliwer realissime försäkratt är icke ens til tenkia på frid, men orsaken som migh hawa beweckt att giwa Eder gradus att stiga så witt neder som uthi resolutione giwne are i blandt alle andre icke den ringeste att Jagh wel märker, mestedelen aff Wort Rixens råhd wara fast aff en annan meningh en både J och iagh i det fallet wara kunna. frvcktar och fore att der det komme til ihlhelningen skvle somlige gierna (att hielpa kriget aff) vthan Caution wara att Contentera Jagh wil ingen beskülla men doch tror Jagh wist att tidernes afflop skal giörra min ord sand, och warder iagh i detta stendernes vtskot fuller kanske mera fornimmandes. J kunna wel besinna huru swårt det skal falle migh att strengia på den saken, som iagh wät att somlige wel funne råhdeligt att remittera, helst medan det skulle bliwa improberat (til äwentyrs) aff dem som der nogot påkomme billigt borde forswara de Consilia som med deras Consens wore tagne, tÿ tet skulle sedan hetas (der det annars en wel affginge) sådant spel allenast wara begunt aff nogra orolige hvwuden och gionnom mine och andre fleres Ambition wara Continuerat Wara. Sedan skulle min osküldige vngdom wara den Calumnie vnderkasta att den icke hade warit Capabel til helsosamt rhåd vthan transporterat aff libidine Dominandi, hawa sådanna fauter begongit. tÿ iagh kan wel sij min sort wara sadan att om nagot welbetenckt och flitigt giors aff mig, så hawa andra der ähran aff, men der nogot försummes som borde tages i acht aff androm, moste skulden wara min. Doch Jagh wil til gud hopas att ded skal alt gå wel aff. tecktes hans gudomeliga wilia att giwa wår flåtta wind hopades iagh att driwa werket så wit att man til äwentyrs, kunde hawa hop nogot mera at obtinera. Jagh beklagar högt den Edle tiden som så onyttigt löper sin kos, men det står nhu intet til endra, vthan moste befalas gud med hop att hans gudomelige almacht som alt hertil sa vnderligen hawer fort werket warder det och i sinom thid forandes til en önskelig vthgong. och wil hermed låta eder förnimma att, ner Jagh ret Considererar edert Consilium moste Jagh det helt aprobera och hawa Eder sake recommenderat, på det i moge giöra Conditiones de beste och säkreste Eder mögligit är. Eder flit, troghet och förstånd är migh nogsamt bekend, der är iagh aldeles vthan sorg att aff eder nogot skal forsvmmas. recommenderar alt så denne tractatz vtgång i gutz och edra hender, beder allenast att i icke will tröttas wed detta beswerliga arbete."

"I have sufficiently understood by your letters how far the peace treaty is advanced, as well as the talks that Monsieur de la Tuillerie has had with you concerning the guarantee. The Danes have since approached, making the offer of Helmstadt; although the last post marks us that they do not want to go further. I would be of your opinion, as being the surest, to fix myself on Halland and Blekinge, and I confess with you that unless we have a real security, we should not think of peace, but on other reasons, which have led me to give you degrees to decend to the point which is marked in the resolution. This is not the least, namely, that I realize that most of our kingdom's senators are of a completely different opinion than you and I can be, in this case. I am even afraid that if the case came to the point of the decision, there would be some who, to put an end to the war, would content themselves with giving it their hands, leaving the guarantee. I am not accusing anyone, but I am certain that time will verify what I say, and I will learn, perhaps, even more, in the present State Committee. You will understand that it will be difficult for me to insist too much on this point, since I know that some will find it convenient to relax from this affair, which perhaps will also be disapproved of by those who, in case of any unfortunate incident, should support the opinions agreed upon with their consent. For if this does not succeed, it will be said that this game was begun only by a few unsettled heads, and that it continued with my ambition and that of some others. Moreover, my innocent youth would be subject to this calumny, that she was not able to take salutary advice, but that, being transported by the desire to dominate, she committed such mistakes: because I foresee that my fate will be such that if I do something carefully and after having thought of it carefully, others will have the honor; but if something is neglected, to which others ought to have thought, the fault will pour upon me. However, I have confidence in God that all will be well; if it pleases His divine goodness to give wind to our fleet, I hope to push the matter to the point of obtaining something more. I am sorry for the loss of so precious a time, which flows instructively: but we are not in a position to stop it. It must be abandoned to the good God, in hope, that His omnipotence, which has so marvelously conducted this work so far, will also bring it to a desirable end. Upon which I must tell you, that when I examine your opinion well, I can not but approve it entirely. You are repeating the whole affair, so that you make the best and most secure conditions possible. Your ability, your genius, and your dexterity are well known to me. On this side I am not apprehensive that you neglect nothing, and that is why I place the result of this Treaty in the hands of God and yours. Please only do not get tired of this difficult work." - Kristina in her letter to Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, dated June 20, 1645

"Dertil medh att Jagh dageligen finner så stora dificulteter i fortsettiande aff kriget så att det wil falla ... medh så ringa medel ett så stort wessen att conducera, hvilket icke vthan hasard att taga dee Conditiones som nhu biudas icke skal affgå. Derhos medh moste och besinnas huru swårt det wil falla att suportera den Calumnien som oss påkomma warder både hos de swenske sielwe så wel som hos fremmande, hvilke alle der freden ginge sär skulle imputera skulden til alles wår ovtsleckliga ambition, den der sig på sielwe orettvissan funderade, och ingen annan finem hade ähn en begirlighet att dominera. och så som Jagh icke heller migh ret forsäkrat om hollendernes Cooperation, altså fruchtar iagh att der desse förreslagne Conditiones icke blewe accepterade, skulle the sökia att bliwa arbitri beleli ac pacis så att deres Jalousie kanske nogot oförmodeliget hos dem cavsera kunde, oansett Jagh förtiger hvad aff pollacken practiceras kan. Sedan det siste och förnemste ähr att contentera sin egen Consientie så att man må kunna för gudh och alle werden betÿga att man sigh til alle skelige fredtzmedel accomoderat hawer."

"I see further so many difficulties in carrying on the war, that I fear we shall have much trouble in attempting so great a task with means so small: and that it would be leaving too much to chance to refuse the conditions offered. We must recollect that, in case peace should be broken off, every one at home or abroad will lay it to the charge of our unmeasured ambition, based on injustice, and with the sole object of empire. And as I don't rely too much on the co-operation of the Dutch, I fear lest, if the proposed conditions are not accepted, they may try to become arbitrators, so that their jealousy may cause them to attempt something untoward; not to mention what the Poles might do. In short, we must make it plain before God and all the world that we applied ourselves to all reasonable means for obtaining peace." - Kristina in her letter to Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, dated June 24, 1645

"Betackar mig ... nådeligen för eder anwände flit och giorda communication: beder j wille därutinnan intet förtröttas, utan så härefter som härtils fortfara i den ifwer, som j hafwe alt härtil temoignerat för mig och Cronans tienst, försäkrande Eder, at ehuruwäl kan ske många tiläfwentijrs skulle söka at denigrera Eder, likwäl skal iag aldrig tillåta at någon skal kunna skada Eder i någon måtto, utan när Gud hielper Eder med hälsan, ock wäl förrättade saker hem igen, skal iag wäl låta i werket påskina at iag är och förblifwer Eder altid med all gunst bewågen."

"I thank you for the trouble you take in conducting this great matter to a successful conclusion, and your communication: I beg you not to grow weary, but continue in the zeal you have manifested till now in my service and that of the kingdom. In return I assure you that though many should attempt, perchance, to blacken you here, I will permit none of them to do you wrong in any respect; on the contrary, should you by the grace of God return in good health and successful, I will let you know by solid results that I am and remain always disposed to favour you." - Kristina in a letter to Johan Adler Salvius, dated December 12, 1646

"Iag hafwer fått twänne Edra skrifwelser, hwilke mig mycket fägnat hafwa, och medan iag denna gången intet hafwer för tidens korthets skuld legenhet därpå at swara; beder fördenskuld at j på mina wägnar och på det aldra högste tacke Mons: d'Avaux för den stora och remarquable tienst, han mig har bewist, och giörer min enskyllan på det flitigaste, at Jag icke denna gången kan swara. Iag har så mycket at giöra, så at iag icke nog kan skrifwa. Iag hoppas at han aldrig lär twifla om min tacksamhet. Med nästa post skal iag intet manquera at complimentera honom. Hwad freds tractaten wedkommer, har iag optäkt Eder bägge min mening och resolution. Pousserer den saken som hon sig best giöra låter. Iag räds at iag lär få så mycket skaffa här hemma, så at iag wäl må tacka Gud at kunna få någorlunda en god fred. J förstån bättre än iag, quam arduum, quamque subjectum fortunæ regendi cuncta onus."

"I have received two letters from you which have pleased me greatly. I have not time to answer them as they deserve; accordingly, I beg you to thank M. D'Avaux for the essential service he has done me, and make my very particular excuses to him for not being able to write to him to-day. I have so much to do just now, that time is not sufficient for all my business. I hope he will never doubt my gratitude. I will not fail to thank him by the first courier. As to the Treaty of Peace, I have declared to both of you my opinion and my determination. Push matters on as best you can. I expect to have plenty to attend to here, so much so that I shall thank God if I am able to obtain, by hook or by crook, a good peace. You know better than me, quam arduum quamque subjectum fortunæ regendi cuncta onus!" - Kristina in a letter to Johan Adler Salvius, dated February 13, 1647

"Ser iag af alle omständigheter wäl, at en part sökia at protrahera Tractaten, åtminstone där de icke alldeles den kunna renversera. ... iag skal wisa all werlden se, at icke heller R. C. förmår allena röra werlden med ett finger, Sapienti sat. Mit bref som härhos fogadt är til eder bägge, måtte j lefwerera åt G. J. O.; och ehuruwäl iag der utinnan tastar eder hårt an, så är han doch allena dermed ment. Lager så at d'Avaux får weta dess Contenta, på det at Fransosener icke fatta wrånge tanckar om mig, utan at de måtte se hwars skulden är. ... när Gud en gång hielper Eder med fred hem, skal edre giorde tienster med Senatoria dignitate recompenseras. J weta sielf at det är den högsta äran som en ärlig man kan aspirera til i wårt Fädernesland, och der såsom någon högre gradus honoris wore, skulle iag ingen sky draga eder den at conferera."

"From all circumstances, I see how a certain person, not being able entirely to break the Treaty, seeks to put it off. ... I will let all the world see that the Chancellor cannot turn the whole world round his finger, sapienti sat. My letter herewith is addressed to both of you, give it immediately to Count Johan Oxenstierna; though I attack him and you equally in it, 'tis meant for him alone — let D'Avaux know the contents, that the French may not think ill of me, but see who is to blame. ... If by God's grace you come back here after the Peace, I will reward you Senatoriâ dignitate. You know it is in our country the highest honour to which an honest man can aspire — were there any higher gradus honoris I would not stick at conferring them upon you." - Kristina in a letter to Johan Adler Salvius, dated April 10, 1647